Film Literature Comparison Odyssey O Brother Where Art Thou

Events in the main sequence of the Odyssey (excluding the narrative of Odysseus'due south adventures) have place in the Peloponnese and in what are now called the Ionian Islands (Ithaca and its neighbours). Incidental mentions of Troy and its house, Phoenicia, Arab republic of egypt, and Crete hint at geographical knowledge equal to, or perhaps slightly more than extensive than that of the Iliad.[1] However, scholars both ancient and modern are divided whether any of the places visited by Odysseus (later Ismaros and before his return to Ithaca) were real.

The geographer Strabo and many others came down squarely on the skeptical side: he reported what the great geographer Eratosthenes had said in the late 3rd century BC: "You volition notice the scene of Odysseus'southward wanderings when you discover the cobbler who sewed upward the purse of winds."[ii]

Geography of the Telemachy [edit]

The journey of Telemachus to Pylos and Sparta no longer raises geographical bug. The location of Nestor's Pylos was disputed in artifact; towns named Pylos were found in Elis, Triphylia and Messenia, and each claimed to exist Nestor's home. Strabo (8.three), citing earlier writers, argued that Homer meant Triphylian Pylos. Modern scholarship, however, generally locates Nestor's Pylos in Messenia. The presence of Mycenaean ruins at the archaeological site of Ano Englianos, or Palace of Nestor, have profoundly strengthened this view. The Linear B tablets found at the site point that the site was called Pu-ro ("Pylos") by its inhabitants.[three]

Identification of Ithaca and neighboring islands [edit]

The geographical references in the Odyssey to Ithaca and its neighbors seem confused and have given rise to much scholarly argument, outset in ancient times. Odysseus's Ithaca is normally identified with the isle traditionally called Thiaki and now officially renamed Ithake, but some scholars have argued that Odysseus'due south Ithaca is really Leucas, and others place information technology with the whole or part of Cephalonia. Lately, Robert Bittlestone, in his book Odysseus Unbound, has identified the Paliki peninsula on Cephalonia with Homeric Ithaca.

Geography of Odysseus's narrative [edit]

"The World according to Homer", co-ordinate to an 1895 map.

The geography of the Apologoi (the tale that Odysseus told to the Phaeacians, forming books 9-12 of the Odyssey), and the location of the Phaeacians' own isle of Scheria, pose quite different issues from those encountered in identifying Troy, Mycenae, Pylos and Ithaca.

- The names of the places and peoples that Odysseus visits or claims to have visited are not recorded, either as historical or contemporary information, in any ancient source independent of the Odyssey.

- What happens to Odysseus in these places, co-ordinate to his narrative, belongs to the realm of the supernatural or fantastic (to an extent that is not true of the residuum of the Odyssey).

- It can be doubted whether Odysseus's story is intended, within the general narrative of the Odyssey, to exist taken every bit true.

- We cannot know whether the poet envisaged the places on Odysseus' itinerary, and the route from each identify to the side by side, as existent.

- Even if the places were envisaged as real, the effects of littoral erosion, silting and other geological changes over thousands of years can modify the landscape and seascape to the point where identification may exist extremely difficult.

For these reasons, the opinions of later students and scholars about the geography of Odysseus's travels vary enormously. It has repeatedly been argued that each successive landfall, and the routes joining them, are real and can be mapped; it has been argued with equal confidence[iv] that they do not exist in the real earth and never can be mapped.

Ancient identifications [edit]

Ancient sources provide a wealth of interpretations of Odysseus' wanderings, with a circuitous range of traditions which affect one another in various ways. Broadly speaking there are two dominant trends. One is that of Euhemerist accounts, which re-wrote mythical stories without their fantastic elements, and were often seen as thereby recovering "historical" records. The other reflects the conventions of foundation myths, whereby stories of a city or institution existence founded in the course of Odysseus' travels often came to have political significance.

Some identifications are common to both groups. The main distinctions betwixt them are in how the identifications were passed downward through the generations, and the uses to which they were put. The well-nigh standard identifications, which are rarely disputed in ancient sources, are:

- land of the Cyclopes = Sicily[5]

- state of the Laestrygonians = Sicily[6]

- island of Aeolus = one or more of the Aeolian Islands off Sicily's north coast[7]

- Scheria, the land of the Phaeacians = Corcyra (modern Corfu), off the west coast of Greece and Republic of albania[8]

- Ogygia, the island domicile of the nymph Calypso = Gaulos, mod Gozo, role of the Maltese archipelago.[9]

Euhemerist accounts [edit]

Euhemerist accounts are generally those plant in writers on antiquarian subjects, geographers, scholars, and historians. The about of import ancient sources are the 1st century geographer Strabo, who is our source for information on Eratosthenes' and Polybius' investigations into the affair; and the novelisation of the Trojan War that goes under the name of Dictys of Crete, which many subsequently writers treated as an authentic historical tape of the war.

The prototypes for this tradition are in the 5th century BC. Herodotus identifies the land of the lotus-eaters as a headland in the territory of the Gindanes tribe in Libya, and Thucydides reports the standard identifications mentioned above.[x] [11] Herodotus and Thucydides practice not actively euhemerise, but simply take local myths at face value for the political importance they had at the time.[12]

Euhemerist accounts become more than prominent in Alexandrian scholarship of the Hellenistic period. Callimachus identifies Scheria as Corcyra, and likewise identifies Calypso's island with Gaulos (modern Gozo, part of Malta).[xiii] His educatee Apollonius of Rhodes too identifies Scheria as Corcyra in his epic the Argonautica.[xiv]

Apollonius' successor equally head of the library of Alexandria, Eratosthenes, wrote a detailed investigation into Odysseus' wanderings. Eratosthenes takes a cynical view, regarding Homer every bit an entertainer, not an educator: "You lot volition detect the scene of the wanderings of Odysseus when you find the cobbler who sewed upwardly the purse of the winds."[xv] This does not mean that he refuses any and all identifications. He conjectures that Hesiod's data about the wanderings (come across below on Hesiod) came from historical inquiries that Hesiod had made.[16] The 2nd century BC poet-historian Apollodorus of Athens sympathises with Eratosthenes, believing that Homer imagined the wanderings every bit having taken identify in a kind of fairyland in the Atlantic; he actively criticises the standard identifications in and around Sicily, and refuses to offer any identifications of his ain.[17]

The 2nd century BC historian Polybius discusses the wanderings in volume 34 of his history. He refutes Apollodorus' idea that the wanderings were in the Atlantic on the ground of Odyssey 9.82, where Odysseus says that he sailed for nine days from Greatcoat Malea in the Peloponnese to the land of the lotus-eaters: it would accept much longer than ix days to achieve the Atlantic. He accepts the standard identifications effectually Sicily, and is the earliest source to identify Scylla and Charybdis explicitly with the Strait of Messina.[18] He too identifies the land of the lotus-eaters as the isle of Djerba (ancient Meninx), off the declension of Tunisia.[nineteen] Polybius is the most euhemerist source to this date: he justifies the description of Aeolus in the Odyssey equally "king of the winds" on the grounds that Aeolus "taught navigators how to steer a form in the regions of the Strait of Messina, whose waters are ... difficult to navigate", and insists that the mythical elements in the wanderings are insignificant in comparing to the historical core.[fifteen]

Strabo, living in the belatedly 1st century BC and early 1st century AD, says that he tries to strike a balance between reading Homer as an entertainer and as a historical source.[xx] He is Euhemerist to the extent that he believes that any hypothesis at all, no matter how outrageous, is more plausible than maxim "I don't know";[21] in this regard he accepts Polybius' arguments completely. Strabo offers the most detailed surviving set of identifications:

- Lotus-eaters: Djerba, following Polybius (1.2.17)

- Cyclops: due south-due east Sicily, near Etna and Lentini (1.2.9); also suggests that Homer "borrowed his idea of the one-eyed Cyclopes from the history of Scythia, for information technology is reported that the Arimaspians are a ane-eyed people" (1.2.ten)

- Aeolus: Lipari, among the Aeolian Islands due north of Sicily

- Laestrygonians: south-due east Sicily (1.2.9)

- land of the Cimmerians: the Bosporus (i.2.9)

- the Ocean: the Black Ocean (ancient Pontus; 1.2.10)

- Sirens: either Cape Faro, past the Strait of Messina; or Sirenussae, a headland in Italy between the Bay of Naples and the Gulf of Salerno; or Naples itself (one.2.12-13)

- Scylla and Charybdis: Strait of Messina (i.two.nine, 1.two.16)

- Ogygia (Calypso's island) and Scheria: "imagined in fantasy" as being in the Atlantic (1.2.eighteen)

Plutarch agrees with Strabo on the location of Calypso's island of Ogygia in the Atlantic, and specifically due west of Great britain.[22] He also repeats what Plato had described as a continent on the opposite side of the Atlantic ( N America ? ),[23] and he adds that from this continent Ogygia was about 900 kilometres / 558 miles distant. Plutarch's business relationship of Ogygia has created a lot of controversy as to whether he was referring to a real or a mythical place. Kepler in his "Kepleri Astronomi Opera Omnia" estimated that "the great continent" was America and attempted to locate Ogygia and the surrounding islands. G. Mair in 1909 proposed that the knowledge of America came from Carthaginian sailors who had reached the Gulf of Mexico. Hamilton in 1934 indicated the similarities of Plutarch's account and Plato's location of Atlantis on the Timaeus, 24E - 25A.[24]

Other sources offer miscellaneous details. The Library wrongly attributed to Apollodorus summarises about of the accounts given to a higher place. Aristonicus, a contemporary of Strabo'southward, wrote a monograph On the wanderings of Menelaus, which influenced Strabo's own discussion.

Finally, the Ephemeris attributed to Dictys of Crete, who claims to have been present at the Trojan War, was probably written in the 1st century CE or perchance a niggling earlier. It falls into a tradition of anti-Homeric literature, based on the supposition that Homer got near things about the Trojan War wrong by making virtuous people wait like villains, and vice versa. It is important considering later historians took Dictys as a historical tape, including Sisyphus of Cos, John Malalas, George Cedrenus, John of Antioch, and others. Many Western mediaeval writers also accepted Dictys (in the Latin summary by Lucius Septimius) every bit the definitive account of the Trojan War.

Co-ordinate to Dictys, Odysseus fled from Troy afterwards existence accused of murdering Aias. He first went north to the Blackness Sea for a while; he sacked the Ciconian town of Ismarus in Thrace on his way back. After visiting the lotus-eaters he went to Sicily, where he encountered iii (or four) brothers, Antiphates, Cyclops, and Polyphemus (and mayhap Laestrygon, according to Septimius), who each ruled a portion of the island. Odysseus and his men were mistreated by each of these kings in turn. Notably, they were imprisoned by Polyphemus when one of Odysseus' men savage in beloved with Polyphemus' daughter (Arene or Elpe) and tried to kidnap her; but they escaped. They passed through the Aeolian Islands, simply the surviving accounts of Dictys practice not give specific locations for the rest of the wanderings. Malalas' account of Dictys, however, tells united states that Circe and Calypso were sisters ruling over neighbouring islands; that Odysseus visited a lake called Nekyopompos ("guide of the dead") near the sea, whose inhabitants were seers; that he passed some rocks called the Seirenidai; and Cedrenus' business relationship seems to place Scheria with Corfu, or at least an isle near Ithaca.[25]

Foundation myths [edit]

Numerous places in Italy and northern Greece as well had aetiological legends about cities and other institutions founded by Odysseus on his various travels. Among these foundation myths the continuation of Odysseus's travels told in the Telegony is at least as important as the wanderings reported in the Odyssey.

The earliest record of a foundation myth connecting Odysseus with Italy is the lines surviving in Hesiod'southward Theogony (1011ff.), which report that Odysseus and Circe had two sons Agrius and Latinus, who ruled over the Etruscans (Tyrsenoi). Latinus is an important figure in many early Italian myths. The lines are not in fact Hesiodic, but they are probably no later than the 6th century BC.[26] [27]

Eastward.D. Phillips gives a very full treatment of myths that placed Odysseus and Telegonus, his son by Circe, in Italy.[28]

Modern views [edit]

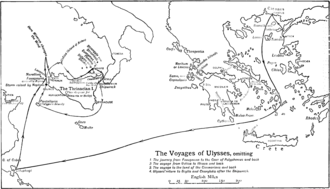

Map of Ulysses' travels from Butler'due south English translation of The Odyssey (1900).

Imaginary places [edit]

The view that Odysseus's landfalls are best treated equally imaginary places is probably held by the majority of classical scholars today.

The mod Greek Homerist Ioannis Kakridis may be compared with Eratosthenes in his arroyo to the problem. He argued that the Odyssey is a work of poetry and not a travel log. To attempt a quick outline of Kakridis'due south views, it is useless to try to locate the places mentioned in Odysseus' narrative on the map; we cannot confuse the narrative of Odyssey with history unless nosotros believe in the existence of gods, giants and monsters. Kakridis admits that ane may indeed enquire what real locations inspired these imaginary places, but i must always conduct in listen that geography is not the main business either of Odysseus (every bit narrator) or of the poet.[29] Similarly, Merry and Riddell, in their late-19th century school edition of the Odyssey, state the post-obit opinion: "Throughout these books [books nine-12] we are in a wonderland, which we shall await in vain for on the map".[xxx] West. B. Stanford, in his mid-20th century edition, comments as follows on book 9 lines 80-81 (where Odysseus says that he met storms off Cape Malea nigh the island of Cythera): "These are the concluding clearly identifiable places in O.'s wanderings. After this he leaves the sphere of Geography and enters Wonderland ..."[31] Thereafter, while frequently referring to ancient opinions on the location of Odysseus'southward adventures, Stanford makes little or no reference to mod theories.

Robin Lane Play a joke on[32] observes of Euboean Greek settlements in Sicily and Italia, "During their first phase in the Due west, c. 800-740, stories of mythical heroes were not already sited at points along the coast of Italian republic or Sicily. It was only later that such stories became located there, every bit if mythical heroes had been driven west or fled from Asia while leaving the sack of Troy." The heroic legends, including an Odyssean geography, served to attach newly founded western communities "to a prestigious ancestry in the Greeks' mythical past." Flim-flam notes that even Circe found a abode on "Monte Circeo" betwixt Rome and Cumae: "just this association began at the earliest in the later sixth century BC. The Etruscan king Tarquin the Proud (c. 530-510) was credited with the settlement and in due form the very 'cup' of Odysseus was shown at the site."[33]

The western Mediterranean [edit]

By contrast with these views, some recent scholars, travelers and armchair travelers have tried to map Odysseus's travels. Modern opinions are so varied in particular that for convenience they need to exist classified, equally do the ancient ones. This article deals first with those who believe, as did many aboriginal authors, that the hero of the Odyssey was driven westward or south-westward from Greatcoat Malea and, more than than nine years after, returned from the west to his native Ionian islands: his landfalls are therefore to exist plant in the western Mediterranean.

For a long fourth dimension the virtually detailed study of Odysseus'due south travels was that of the French Homeric scholar Victor Bérard.[34] Although adopting the full general frame of reference of the ancient commentators, Bérard differed from them in some details. For Bérard the country of the Lotus-Eaters was Djerba off southern Tunisia; the country of the Cyclopes was at Posillipo in Italian republic; the island of Aeolus was Stromboli; the Laestrygonians were in northern Sardinia; Circe's domicile was Monte Circeo in Lazio; the archway to the Underworld was near Cumae, only where Aeneas institute it in the Aeneid; the Sirens were on the coast of Lucania; Scylla and Charybdis were at the Strait of Messina; the Island of the Sun was Sicily; the homeland of Calypso was at the Straits of Gibraltar. From there Odysseus'south route took him to Scherie, which Bérard, like so many of his ancient predecessors, identified with Corcyra.

Bérard's views were taken as standard in the 1959 Atlas of the Classical World by A. A. M. van der Heyden and H. H. Scullard.[35] They were adopted in whole or in role past several later writers. Michel Gall, for instance, followed Bérard throughout except that he placed the Laestrygonians in southern Corsica.[36] Ernle Bradford had meanwhile added some new suggestions: the state of the Cyclopes was effectually Marsala in western Sicily; the island of Aeolus was Ustica off Sicily; Calypso was on Republic of malta.[37] The Obregons, in Odysseus Airborne, follow Bradford in some identifications but add several of their own. The Lotus Eaters are in the Gulf of Sidra; the Cyclops and Aeolus are both to exist found in the Balearic Isles; the isle of Circe is Ischia in the Bay of Naples; most unexpectedly, Scherie is Republic of cyprus.[38]

Translator Samuel Butler developed a controversial theory that the Odyssey came from the pen of a young Sicilian adult female, who presents herself in the poem as Nausicaa, and that the scenes of the verse form reflected the declension of Sicily, specially the territory of Trapani and its nearby islands. He described the "evidence" for this theory in his The Authoress of the Odyssey (1897) and in the introduction and footnotes to his prose translation of the Odyssey (1900). Robert Graves elaborated on this hypothesis in his novel Homer'southward Daughter.

Effectually Hellenic republic [edit]

A minority view is that the landfalls of Odysseus were inspired by places on a much shorter itinerary forth the declension of Greece itself. Ane of the primeval to propose any locations here was the 2nd century AD geographer Pausanias who, in his Description of Greece, suggested that the nekyia took place at the river Acheron in due north west Greece, where the Necromanteion was subsequently built.[39] Yet the location was overlooked or dismissed by many afterward, until the archaeologist Sotirios Dakaris excavated the site, beginning in 1958. He establish evidence of sacrifices to the dead that matched Homer's description of those fabricated by Odysseus.[40] Subsequently, the location was accepted by others every bit that described by Homer.[41] [42]

The Ambracian Gulf and the island of Levkas (foreground, centre), around which Severin suggested locations for the Sirens, the Wandering Rocks, Scylla, Charybdis and the island of Helios's cattle.

Working on the assumption that the discoveries at the Acheron could challenge the traditional assumptions about the Odyssey's geography, Tim Severin sailed a replica Greek sailing vessel (originally built for his effort to retrace the steps of Jason and the Argonauts) forth the "natural" road from Troy to Ithaca, following the sailing directions that could exist teased out of the Odyssey. Along the way he constitute locations at the natural turning and dislocation points which, he claimed, agreed with the text much more closely than the usual identifications. Notwithstanding, he also came to the conclusion that the sequence of adventures from Circe onwards derived from a separate itinerary to the sequence that ended with the Laestrygonians and was mayhap derived from the stories of the Argonauts. He placed many of the later episodes on the north w Greek coast, near the Acheron. Along the style he institute on the map Cape Skilla (at the entrance to the Ambracian Gulf) and other names that implied traditional links with the Odyssey. Severin agrees with the common opinion that the Lotus Eaters are in Northward Africa (although he placed them in modern Libya rather than Tunisia) and that Scherie is Corcyra.[43]

A key function of Severin's thesis is that whilst the text of the Odyssey contains many identify names to the east and south of Hellenic republic, there are very few identifiable references to places to the w. As a result, he questions whether the western Mediterranean was known about at the time the original legends emerged (which he estimated to exist some centuries earlier Homer composed the poem) and so consequently he doubted whether the stories had their origins in that location. In addition he noted that the Acheron is marked on the map, just traditionally ignored, whilst in the Argonautica of Apollonius of Rhodes the Argonauts' home voyage took them into the Adriatic and Ionian Seas, corresponding to a north west Greek location for many of the subsequently adventures.[43]

Atlantic Ocean and other theories [edit]

Strabo's opinion (mentioned higher up) that Calypso's island and Scherie were imagined by the poet as being "in the Atlantic Ocean" has had significant influence on modern theorists. Henriette Mertz, a 20th-century author, argued that Circe'due south island is Madeira, Calypso's isle i of the Azores, and the intervening travels record a discovery of N America: Scylla and Charybdis are in the Bay of Fundy, Scherie in the Caribbean.[44]

Enrico Mattievich of UFRJ, Brazil, proposed that Odysseus'southward journey to the Underworld takes place in South America. The river Acheron is the Amazon; later a long voyage upstream Odysseus meets the spirits of the dead at the confluence of the rio Santiago and rio Marañon.[45] 2 centuries ago, Charles-Joseph de Grave argued that the Underworld visited by Odysseus was the islands at the mouth of the river Rhine.[46] A more farthermost view, that the whole geography of the Iliad and the Odyssey can be mapped on the coasts of the northern Atlantic, occasionally surfaces. According to this, Troy is in southern England, Telemachus'due south journey is in southern Spain, and Odysseus was wandering the Atlantic coast.[47] Finally, a recent publication argues that Homeric geography is to be found in the sky, and that the Iliad and the Odyssey can be decoded as a star map.[48]

See also [edit]

- Homeric scholarship

Notes [edit]

- ^ Setting aside the geographical cognition shown in the Catalogue of Ships and Trojan Battle Order, which are extremely detailed and precise, merely may take an orally transmitted history different from the residuum of the Iliad narrative.

- ^ Strabo 1.2.15, quoted past Moses I. Finley, The Earth of Odysseus, rev. ed. 1976:33. For the oxhide bag of winds, see "Aeolus", in Odyssey X.22 ff.

- ^ Simpson and Lazenby, p. 82. See likewise the department headed Atlantic Body of water theories.

- ^ Recently by Robin Lane Play a joke on, Travelling Heroes in the Epic Age of Homer, 2008, ch. "Finding Neverland"; Lane summarizes the literature in notes and bibliography..

- ^ Earliest sources for this identification: Euripides' play Cyclops, set near Mount Etna; and Thucydides half-dozen.two.1.

- ^ Earliest source for this identification: Thucydides half dozen.two.1.

- ^ Primeval source for this identification: Thucydides 3.88.

- ^ Earliest source for this identification: Thucydides 1.25.iv. It is notable that the Archaic verse form the Naupactia referred to Corcyra in the context of the story of Jason, which was earlier in the mythic age than Odysseus, but does non seem to have identified it with Scheria (Naupactia fr. 9 West).

- ^ Strabo seven.iii.6, referencing Callimachus' account in relation to Euhemerus. Also, Bradford, Ernle (1963), Ulysses Institute

- ^ Herodotus 4.177.

- ^ Thucydides 1.25, 3.88, 6.ii.

- ^ On the political importance of Corcyra'due south identification with Scheria, see east.m. C.J. Mackie 1996, "Homer and Thucydides: Corcyra and Sicily", Classical Quarterly 46.1: 103-13.

- ^ Strabo seven.three.6.

- ^ Argonautica four.983ff.

- ^ a b Strabo one.ii.15.

- ^ Strabo 1.two.14.

- ^ Strabo 1.2.37, 7.3.6.

- ^ Strabo ane.two.15-sixteen.

- ^ Strabo 1.2.17.

- ^ Come across particularly i.2.iii, one.2.17, ane.two.19.

- ^ Strabo 1.2.37.

- ^ Plutarch, Apropos the face which appears in the orb of the moon, 941A-B.

- ^ Plato, Timaeus, 24E - 25A

- ^ Introductory notes on Plutarch'south "Apropos the Face Which Appears in the Orb of the Moon" at the Loeb Classical Library, particularly notes on p21, p22 and p23.

- ^ This summary is based on a comparison of Septimius (5.15, 6.5) with Malalas (five.114-122 Dindorf).

- ^ J. Poucet 1985, Les origines de Rome (Brussels), p. 46 n. 27.

- ^ T.J. Cornell 1995, The Beginnings of Rome (London), p. 210.

- ^ East.D. Phillips 1953, "Odysseus in Italy", Journal of Hellenic Studies 73: 53-67.

- ^ Ελληνική Μυθολογία, vol. 5: The Trojan War (1986) Ekdotike Athenon, Athens. Kakridis compares the effort to locate Circe'southward island to locating the hut of the seven dwarves.

- ^ Stanford (1947), p. 352.

- ^ Stanford (1947), p. 351.

- ^ Fox, Travelling Heroes in the Ballsy Age of Homer, 2008, ch. "Finding Neverland" p.170ff..

- ^ Play a trick on 2008:173, noting Livy i.56.2; Polybius iii.22,xi, and Strabo v.3.six and commentaries.

- ^ Bérard (1927–1929); Bérard (1933).

- ^ Encounter map Archived 2007-01-27 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Lessing (1970).

- ^ Bradford (1963).

- ^ Obregon (1971).

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece: 1.17.5 "Virtually Cichyrus is a lake called Acherusia, and a river called Acheron. There is also Cocytus, a about unlovely stream. I believe it was because Homer had seen these places that he made bold to describe in his poems the regions of Hades, and gave to the rivers there the names of those in Thesprotia."

- ^ Vanderpool, Eugene "News Alphabetic character from Greece" in American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 65, No. 3 (Jul., 1961), p. 302

- ^ Besonen, Marking R., Rapp, George(Rip) and Jing, Zhichun "The Lower Acheron River Valley: Aboriginal Accounts and the Irresolute Mural" in Hesperia Supplements, Vol. 32, Mural Archaeology in Southern Epirus, Greece one (2003), p. 229

- ^ Severin (1987) folio 193

- ^ a b Severin (1987).

- ^ Mertz (1964); encounter map Archived 2005-12-xviii at the Wayback Automobile.

- ^ Mattievich (1992); meet map. Mattievich is a physicist at Rio de Janeiro University.

- ^ de Grave (1806).

- ^ Cailleux (1879); Wilkens (1990); run into map Archived 2007-02-24 at the Wayback Machine. Wilkens supposes that the oral poetry underlying the Iliad and Odyssey was originally Celtic (see Where Troy Once Stood).

- ^ Johnson (1999)

Bibliography [edit]

- Ballabriga, Alain (1998), Les fictions d'Homere. L'invention mythologique et cosmographique dans l'Odyssee, Paris: PUF

- Bérard, Victor (1933), Dans le sillage d'Ulysse, Paris

- Bérard, Victor (1927–1929), Les Navigations d'Ulysse, Paris

- Bérard, Victor (1927), Les Phéniciens et l'Odyssée, Paris

- Bradford, Ernle (1963), Ulysses Found

- Cailleux, Théophile (1879), Pays atlantiques décrits par Homère: Ibérie, Gaule, Bretagne, Archipels, Amériques; théorie nouvelle, Paris: Maisonneuve

- de Grave, Charles-Joseph (1806), République des Champs élysées, ou, Monde ancien: ouvrage dans lequel on démontre principalement que les Champs Élysées et l'Enfer des anciens sont le nom d'une ancienne république d'hommes justes et religieux, située a l'extrémité septentrionale de la Gaule, et surtout dans les îles du Bas-Rhin; que cet Enfer a été le premier sanctuaire de l'initiation aux mỳsteres, et qu'Ulysse y a été initié ...; que les poètes Homère et Hésiode sont originaires de la Belgique, &c., Ghent

- Hennig, R. (1934), Die Geographie des homerischen Epos, Leipzig

- Heubeck, A., eds.; et al. (1981–1986), Omero, Odissea, Rome (English language version: A. Heubeck, South. West and others, A commentary on Homer's Odyssey. Oxford, 1988-92. 3 vols.)

- Johnson, Laurin R. (1999), Shining in the Ancient Body of water: The Astronomical Ancestry of Homer's Odyssey, Portland, OR: Multnomah Firm, ISBN0-9669828-0-0

- Lessing, East. (1970), The Adventures of Odysseus (contribution by Michel Gall)

- Malkin, Irad (1998), The Returns of Odysseus, Berkeley: University of California Press

- Mattievich, Enrico (1992), Viagem ao inferno mitológico

- Mertz, Henriette (1964), Vino Dark Ocean

- Obregon, E. (1971), Ulysses Airborne

- Romm, James (1994), The Edges of the Globe in Ancient Idea, Princeton: Princeton University Printing

- Roth, Hal (2000), We Followed Odysseus

- Severin, Tim (1987), The Ulysses Voyage: Sea Search for the Odyssey

- Simpson, R. Hope; Lazenby, J. F. (1970), The Catalogue of Ships in Homer's Iliad, Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Stanford, W. B. (1947), The Odyssey of Homer, London: Macmillan

- Stanford, West. B.; Luce, J. Five. (1974), The Quest for Odysseus, New York: Praeger

- Voss, Johann Heinrich (1804), Alte Weltkunde, Jena, Stuttgart

- Wilkens, Iman (1990), Where Troy Once Stood, London: Rider

- Wolf, A.; Wolf, H.-H. (1983), Die wirkliche Reise des Odysseus [The Real Journey of Odysseus], München: Langenmüller

External links [edit]

Ancient sources [edit]

- Apollonius, Argonautica

- Herodotus, History 4.177

- Homer, Odyssey

- Plutarch, Apropos the Face Which Appears in the Orb of the Moon

- Strabo, Geography ane.2.1-1.2.23, 1.2.24-1.2.forty

- Thucydides, History i.25, iii.88, 6.2, likewise in Greek 1.25, 3.88, vi.two

Modern views [edit]

- Jonathan Burgess'southward page on the travels of Odysseus

- Jean Cuisenier's attempt to find Odysseus' route

Maps [edit]

- "The World of Homer" (based on V. Bérard) from A. A. M. van der Heyden, H. H. Scullard, Atlas of the classical earth (London: Nelson, 1959)

- Map of the geography of the Odyssey based on the ideas of Iman Wilkens

- University of Pennsylvania, Section of Classical Studies, Interactive Map of Odysseus' Journey

- Odysseus' Journeying: A map of the locations in Homer'southward Odyssey an ArcGIS storymap

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geography_of_the_Odyssey

0 Response to "Film Literature Comparison Odyssey O Brother Where Art Thou"

Post a Comment